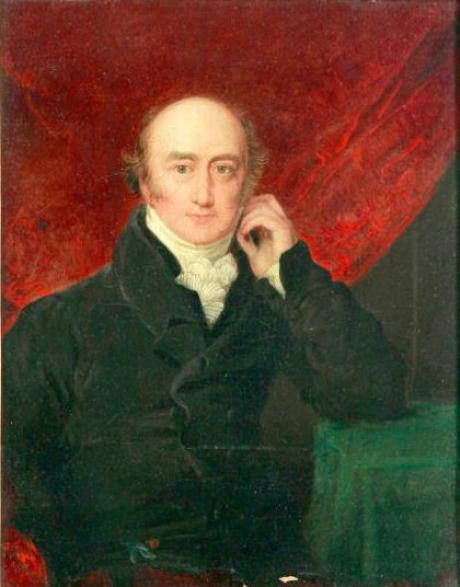

Mezzotint, Charles Turner, 1827

George Canning, (1770–1827), prime minister and parodist, was born in Marylebone, Middlesex, on 11 April 1770, the son of George Canning (1736–1771) and his wife, Mary Ann Costello (1747?–1827). His parents were both Irish; he described himself as ‘an Irishman born in London’ (Temperley, Life, 16) and identified himself with the Irish demand for Catholic emancipation, but he visited Ireland only once, in 1824. His father was the eldest son of Stratford Canning (1703–1775), a cantankerous protestant gentleman with a modest estate at Garvagh in co. Londonderry and a house in Dublin. George senior took his BA at Trinity College, Dublin, in 1754, but was sent by his father to London in 1757 to prevent him making an unacceptable marriage. There, on an allowance of £150 p.a., he read for the bar and was called at the Middle Temple in 1764. But ‘it would appear that [he] was a lover of literature and pleasure, and excessively averse to the dull study of the profession to which his life was doomed to be devoted’ (Rede, 8 n.). His circle included journalists, actors, and politicians, and he was a friend and supporter of Wilkes. He published at least one political pamphlet and some verses, including a translation (1766) of five books of Polignac's Anti-Lucretius, which he dedicated to Queen Charlotte as ‘a poem, calculated to promote the cause of religion, and virtue, by overturning the pillars of immorality, and atheism’. He ran up large debts, which his father paid off in return for his renouncing his right to inherit the family estates. His wife, whom he married in Marylebone parish church on 21 May 1768, was beautiful, spirited, and on her mother's side from a good family—her guardian and maternal grandfather was Colonel Guydickens of Wigmore Street, formerly known as Guy Dickens, who had been British envoy in Berlin (1740–41), Stockholm (1742–8), and St Petersburg (1749–55), and whose son Gustavus was a gentleman usher in the queen's household—but she had no money of her own.

Childhood and education

George was the second of their three children and the only one to reach adulthood. On the boy's first birthday George senior died. Stratford's allowance to his son lapsed, and he would allow Mary Ann only £40 p.a., which was given for the children and on condition that she stayed in England. Her resources were so inadequate that she decided to try to make a living as an actress. Garrick, perhaps at the request of the queen, gave her a chance at Drury Lane in November 1773, but she did not succeed there. She then turned to provincial theatres, where she had better luck. By becoming an actress she excluded herself from respectable society, and she soon made matters worse by becoming the mistress of the dissolute actor Samuel Reddish. The couple had five children and she called herself Mrs Reddish. Canning's early years were spent touring provincial theatres with his mother and Reddish, and he later reminisced about a humble school at which he had within a month ‘got through … by far the greater part of a gingerbread alphabet’ (The Microcosm, 1, 1786, 434).

In 1778, however, the Canning family came dramatically to the boy's rescue. They provided money to pay for his maintenance and education, and his uncle Stratford, well established as a merchant banker in the City, became his guardian and took him into his home in Clement's Lane. He was sent to his first respectable school, Hyde Abbey, Winchester, in 1778 and to Eton College in 1782. On the death of his paternal grandmother in 1786 he ‘came into possession of the fortune left me by my grandfather, about 400l. per annum’ (Raven, 51). His uncle, the younger Stratford, died in May 1787, and Canning's legal guardian now became William Borrowes, Stratford's business partner. He continued to spend much time with Stratford's widow, Hetty (Mehitabel), and her family, who moved to Wanstead; but, especially as he lost sympathy with her whig views, he felt his closest family ties with his aunt Elizabeth and her husband, the Revd William Leigh, who lived first in Norwich and then at Ashbourne Hall in Derbyshire.

It was part of the arrangement of 1778 that Canning was not allowed to see his mother, of whom he was clearly very fond. However, they wrote to each other regularly. In 1783 she married Richard Hunn, a draper of Plymouth, who then himself took up acting and with whom she had at least three more children. Only in 1786 was Canning permitted to see her again. When he received his inheritance, he persuaded his guardian to make his mother an allowance of £50 out of it. For the rest of her life, which lasted until March 1827, he supported her and her children financially and in other ways, and wrote to her frequently and informatively, but she remained a source of embarrassment to him and he saw her only rarely and circumspectly.

Canning's Eton career was a triumph almost without parallel. He proved a brilliant classic, came top of the school, and excelled at public orations. He gathered round him a circle of friends who remained close to him throughout his life, especially John Hookham Frere and Charles Ellis. He and Frere, with John (Easley) Smith and Robert (Bobus) Smith, wrote and published a magazine called The Microcosm (1786–7), made up of elegant and witty articles that scoffed at literary criticism, sentimental novels, aristocratic pretension, and the like. This publication achieved remarkable fame and was four times reprinted. Canning's part in it, though he had written under the pseudonym Gregory Griffin, was known and widely admired, not least by George III and Queen Charlotte.

From Eton Canning went up in 1787 to Christ Church, Oxford, where his successes continued. He won college and university prizes for Latin verse and was made a student (fellow) of his college. He acquired many new friends, mostly of high social standing: pre-eminently Robert Banks Jenkinson, later to be his political colleague, on and off, for nearly forty years; Lord Boringdon, owner of Saltram House in Devon; Lord Morpeth, heir to the earldom of Carlisle and to Castle Howard; Lord Holland; Charles Moore, son of the wealthy archbishop of Canterbury; William Sturges Bourne; and Lord Granville Leveson-Gower, son of the marquess of Stafford. Some of them, with Lord Henry Spencer, whom Canning had known at Eton, formed with less well-connected undergraduates a select college debating society, the members of which sported a uniform that paid homage to Demosthenes, Cicero, Pitt, and Fox. Cyril Jackson, the dean of Christ Church, who was to give guidance to Canning for many years, suggested to him that he should resign from the club because his being a member implied that he wanted to go into politics rather than to succeed at his intended profession, the law. Canning complied, to the annoyance of his friends, writing:

I am already, God knows, too much inclined, both by my own sanguine wishes and the connections with which I am most intimate, and whom I above all others revere, to aim at the House of Commons, as the only path to the only desirable thing in this world, the gratification of ambition; while at the same time every tie of common sense, of fortune, of duty, draws me to the study of a profession. (Newton, 24–5)

The incident encapsulates Canning's predicament: how could a man, however talented, whose origins were dubious and income small, aspire to a political career when MPs were not paid and parliamentary candidates almost always had to shell out large sums to be elected, and when it was axiomatic that nearly every minister would be a peer or the son of a peer?

Canning as disciple of Pitt, 1792–1801

Canning had entered Lincoln's Inn in 1787 and in 1790–92 read seriously for the bar. But he could not be content with making a legal career, and in the summer of 1792 he decided after all to seek a seat in the Commons. His goal, he said, was to become a privy councillor ‘at thirty’—an ambition he was to achieve. His views while at Eton and Oxford had been whiggish, strengthened by the example of his father and by his guardian Stratford Canning's friendship with the opposition leaders—Fox had willingly given advice about the young man's career, and Sheridan regarded him as his élève. Canning wrote verses scoffing at Jenkinson's Pittite stance in the Regency crisis, and his attitude during the first three years of the French Revolution was that a nation was entitled to establish a republican government if it saw fit, and that the experiment was one from which Britain would be able to draw useful lessons. He enjoyed taking part in the debates of popular societies in London. George III was reported as saying late in 1792 that ‘Mr. Canning's republican principles had done great harm at Christ Church’ (Marshall, 26). But by then Canning had aligned himself with Pitt. On 26 July 1792, having received encouragement through intermediaries, he wrote to the prime minister in the strictest confidence saying

that however I was in habits of friendship and familiarity with some of the most eminent men in Opposition, yet I was in no way bound to them by any personal or political obligation, but felt myself perfectly at liberty to choose my own party.

He had not the means to ‘do anything towards bringing myself into Parliament, nor should I like to be brought in by an individual … it was with himself personally that I was ambitious of being connected’. Pitt replied warmly, expressing himself happy to ‘facilitate’ Canning's entry into the Commons when an ‘opening’ presented itself. The two men met on 15 August, and the understanding was confirmed, the prime minister accepting that Canning might take a different stance from his own on the Test Act and on ‘speculative subjects especially’ so long as he showed ‘a general good disposition towards Government’ (ibid., 33–7).

When this agreement became generally known, Canning was accused of betraying both his friends and his principles, and the charge was repeated throughout his career. He explained his motives at length, but even so they are not entirely clear. In some respects his opinions were changing: the course of the revolution had persuaded him that to embark on constitutional reform was too risky, and he particularly criticized Sheridan and his friends for founding the Association of the Friends of the People in April 1792. From this time he consistently defended the unreformed electoral system. His move towards Pitt must have been encouraged by his friendship with Jenkinson and other supporters of government, perhaps especially the Leighs. He must have realized that there was more room for an able young commoner in Pitt's entourage than in Fox's, and that Pitt alone was in a position to procure him a political career on his own terms, terms which no other impecunious aspirant of the time dreamed of proposing. He wanted to be not merely an MP but a minister, a professional politician in an age that expected this ambition, in the rare cases where it existed, to be concealed. This unique approach paid off. In March 1793, in accordance with his principles as stated to Pitt, he refused the offer of a seat from the duke of Portland, despite the duke's political importance, growing sympathy with the government, and readiness to bear the costs of election. However, he took care to retain good relations with the duke, writing verses for his installation as chancellor of the University of Oxford in July 1793. In the same month he became, through Pitt's good offices, MP for Newtown in the Isle of Wight.

Frere said Canning

had much more in common with Pitt than anyone else about him, and his love for Pitt was quite filial, and Pitt's feeling for him was more that of a father than of a mere political leader. I am sure that from the first Pitt marked Canning out as his political heir. (Thorne, 3.380)

Although Canning was to disagree with Pitt's political strategy during the Addington ministry, the compact made between them in 1792 was broken only by Pitt's death in 1806, if then. Canning declared in 1812, ‘my political allegiance lies buried in his grave’ (Therry, 6.326), and claimed always to pursue the line that his mentor would have taken.

The friendship was obvious to all once Canning entered the Commons. After some moderately successful early speeches he was asked to second the address on 30 December 1794. On that and later occasions he distinguished himself in defence of the government's war policy. On 16 June 1795 he confessed to Pitt his hopes of office on grounds both of ambition and poverty, but it took the prime minister some time—from Canning's point of view too long—to find him an appropriate place. It was not until January 1796 that Canning took up one of the two under-secretaryships at the Foreign Office under Lord Grenville. Pitt and Grenville had gone to great trouble to make this opening for him: Aust, the previous under-secretary, had been found another post and promised a pension for his wife.

This was one of the most onerous of all government offices, though it brought with it a salary of only £1500 a year. Canning was so swamped by dispatches that he had to work far into the night and give up much of the hectic social round of soirées, dinners, and theatregoing that he had described in his letter-journal written for the Leighs from November 1793 to August 1795. At the general election of 1796 Pitt procured for him, at no cost and without conditions, a seat at Wendover. The war was now going so badly that negotiations with France were initiated: from October to December 1796 his friend the earl of Malmesbury, accompanied by George Ellis, cousin of Charles, was in Paris, and from July to September 1797 in Lille, attempting unsuccessfully to treat with the Directory. The king and Grenville disapproved of the second mission and Canning found himself the channel both for the foreign secretary's discouraging instructions to Malmesbury and for Pitt's ‘most private’ and more constructive letters to him. Perhaps as a reward for his discretion and dexterity, Pitt appointed him in September 1797 to the clerkship of the alienations, a sinecure worth £700 p.a.

Canning now became the principal mover in a unique project to commend the policies of the government and condemn the revolutionary cause by the publication of a journal, The Anti-Jacobin. It had Pitt's blessing, and he contributed to it in a small way; its editor was William Gifford, and Canning's main collaborators were Frere and George Ellis. It appeared every Monday from 20 November 1797 to 9 July 1798. It owed much of its fame to verses written by Canning in whole or part, some of them parodies of poets who supported the opposition, such as ‘The Friend of Humanity and the Knife-Grinder’, mocking Southey and the idealization of the poor. Another parody of Southey ended:

Reason philosophy fiddledum diddledum,

Peace and Fraternity higgledy piggledy.

In ‘New Morality’, which appeared in the last issue, Canning and Frere ridiculed a whig's foreign policy:

A steady patriot of the world alone,

The friend of every country—but his own.

Apart from verses, the paper contained extensive sections of news and attacks on other journals' misrepresentations. It sold the considerable number of 2500 copies, attracted a lot of notice both admiring and hostile, and was evidently justified in its claim to have helped to swing public opinion in favour of the ministry and the war. Although it was all anonymous, it was generally known that Canning was its inspiration. During the same period he further assisted government propaganda by approaching the cartoonist Gillray. He had been impatient to see himself caricatured, which occurred for the first time late in 1796. In the following year he took to suggesting subjects to Gillray, and helped procure him a pension.

More conventionally, Canning as under-secretary made notable speeches in support of the government's foreign policy, among which that of 11 December 1798 was the first he published. It led Lord Minto to call him ‘a very rising as well as aspiring person in England’ (Thorne, 381). He spoke on several occasions in support of the abolition of the slave trade and succeeded on 3 April 1798 in carrying a resolution (with no legal force) to prevent the cultivation of new land in the West Indies by slave labour. In the following year he defended the proposed union with Ireland as a necessary measure and one that would make possible Catholic emancipation.

In March 1799 Canning's wish to be released from ‘three years of slavery’ (Thorne, 381) and ‘the disagreeableness’ of serving Grenville (Hinde, 57) was satisfied by his appointment as a commissioner of the Board of Control for India; but he remained discontented and hoped to be made a secretary of state. In May 1800 he received instead the additional office of joint paymaster, which carried with it an ‘admirable’ house and membership of the privy council. By this time he was seen as the head of a small party of MPs whose votes he expected to control and for whom he sought office: he had, for example, procured for Frere the succession to his under-secretaryship, for which he proved totally unfitted. It was a unique group in being led by a person who held only minor office and had neither fortune nor social standing. Most of his political friends were also his personal friends, attracted to him at school or university by his brilliance, the ‘vivacity of his conversation’ (Newton, 17), his flights of fancy, and his effervescent sense of fun. They were amused, as others were not, by his habit of bestowing unflattering nicknames on all and sundry, his elaborate practical jokes, and the wit and sarcasm that he directed against those he thought foolish or mistaken. At first too histrionic, he was developing into a great speaker: his height, good looks, jet-black hair, penetrating eye, and sonorous voice gave him a commanding presence; using very few notes, he knew how to marshal an elaborate argument in long sentences of involved syntax, passing easily through light humour and withering invective to an eloquent peroration.

Pitt declared that all Canning now needed to enable him to lead a party with success was to make a good marriage. It is not known that he had any sexually significant relationships with women until in June 1799 he met and was attracted by the princess of Wales, now separated from the prince. She apparently made a pass at him, and the brief liaison, innocent though it seems to have been, was to cause him difficulties when the prince came to the throne in 1820. Fortunately, in August 1799 he went to stay at Walmer Castle, Pitt's house, as warden of the Cinque Ports, where he met Joan Scott (d. 1837), a girl of about twenty-two with a fortune generally put at £100,000. He fell in love with her. Joan had expected to be alarmed by Canning, ‘to be wearied and oppressed by constant endeavours at shining in conversation, by unmerciful raillery and I know not what’ (Hinde, 74), but instead found him captivating. Her parents were dead and she regarded her eldest sister's husband, the marquess of Titchfield, heir to the duke of Portland, as her guardian. He made the predictable objections, but Joan eventually overrode them, and the marriage took place by special licence at Titchfield's house is Grosvenor Street on 8 July 1800, solemnized by uncle Leigh, with Frere as best man and Pitt as a witness. Canning bought a country house, South Hill, near Bracknell, which he had refurbished by Soane, and his wife became pregnant. Their son (Charles) George was born on 25 April 1801.

Political difficulties, 1801–1807

Since 1778 Canning's career had advanced spectacularly and with scarcely a set-back. In February 1801 it went into reverse, when Pitt resigned after the king refused to allow him to propose Catholic emancipation, which he considered himself honour-bound to do. He was succeeded by Addington, whom Canning regarded with contempt and delighted to ridicule. Pitt asked his followers to join the new ministry, but Canning decided that he could not do so, though he was induced by Pitt to send a letter of support. However, he soon began attacking the new prime minister and his government, calling it ‘a conspiracy against all the talents of all sides, and sorts’ (Thorne, 383). His successor as paymaster, Lord Glenbervie, described on 1 April 1801 the hostility he had aroused:

I find the town is full of abuse on Canning. His hot-bed promotions, his saucy manners, and his satirical songs and indiscreet epigrams and buffoonery have already indisposed almost all Pitt's friends. … His conduct has opened many mouths of friends and foes, which had been kept sealed by the knowledge of Pitt's favour or the dread of his own wit. He now may perhaps long repent, though he will probably never subdue the indiscretion of that prurient and boyish vanity which postpones every consideration of decorum, respect for yourself as well as others, and good nature, to the momentary fame and applause of a good thing or an attempt at one. (ibid., 382)

Canning disapproved of the government's policy of making peace with France but was persuaded to absent himself from the debate on the preliminaries in November. At the general election of 1802 he had to buy a seat at Tralee.

Canning continued to regard Pitt as his leader and hero, promoting a birthday dinner for him on 28 May, attended by 975 persons, for which he wrote the song ‘The Pilot that Weathered the Storm’. On 8 December he made a passionate defence of Pitt in the Commons against an attack by Sheridan: ‘Away with the cant of “measures, not men”, the idle supposition that it is the harness and not the horses that draw the chariot along’ (Hinde, 113). But he could not persuade Pitt to take the role that he and his followers cast for him, of heading an opposition to displace Addington, even when war broke out again in May 1803. Canning, so conscious of being restrained and frustrated by his loyalty to Pitt, could not, it seems, understand that Pitt felt himself similarly caught in a false position by his obligations to the king. Canning continued to show animus against Addington and all those who had joined his ministry, especially two Pittites of his own age who had thereby beaten him into the cabinet: Viscount Castlereagh, who in 1802 had become president of the Board of Control, and his old Christ Church friend Jenkinson, who was foreign secretary throughout the ministry and became Lord Hawkesbury in 1803. When Pitt finally returned to office in May 1804, retaining many supporters of Addington, Canning received only the minor but well-paid post of treasurer of the navy. He took pride in the part he had taken in giving Nelson the instructions that made possible the victory at Trafalgar, but he was understandably disaffected at being excluded from the cabinet. Though Pitt promised to find a way of bringing him into it, he had not done so by the time he died in January 1806.

Canning was prepared to remain in office under the new ministry of Grenville, which included both Fox and Addington (now Lord Sidmouth), but he was virtually dismissed and went into opposition. He was very soon concocting—with Castlereagh, Hawkesbury, and Spencer Perceval—a scheme to get the Pittites back into office. In the summer of 1806 they appealed directly to the king behind the ministry's back and received a favourable though temporizing answer. Grenville and other ministers would have liked to capture Canning at least, recognizing that he would greatly strengthen them in the Commons, but in August he refused to join unless guaranteed five places for Pittites in the cabinet. Just after Canning's refusal Fox died, and the government called a general election at which Canning was elected for his old seat at Newtown, this time at considerable expense to himself. He now sold South Hill and took his family to reside at Hinckley, Leicestershire. This apparently bizarre decision was provoked by the serious lameness of his son George, which a Mr Chesher of Hinckley was believed to be the best person to treat.

Foreign secretary, 1807–1809

In the new year the situation was entirely changed by the rupture between George III and Grenville over a bill to allow Roman Catholics to hold commissions in the army. The king, confident of Pittite support, dismissed the ministry. It was replaced by a government under the nominal headship of the ailing duke of Portland, in which, after much manoeuvring, Canning was appointed foreign secretary on 25 March 1807. Another general election followed at which Canning was provided with a Treasury seat at Hastings. He at once emerged as the government's chief spokesman in the Commons: his speech of 30 June was described by Perceval, the leader of the house, as ‘one of the most brilliant speeches which he or any other man ever delivered’ (Thorne, 388–9). He also appeared to dominate the cabinet. Britain, though perhaps secure in the control of the sea, ‘never stood more alone’. In the previous year Napoleon had promulgated his Continental System, intended to cut off all British trade with the entire continent. His annihilation of Prussia at Jena in October 1806 was followed in June 1807 by his destruction of the Russian army at Friedland; and his meeting at Tilsit with Tsar Alexander on 9 July was rightly taken to presage an alliance between them against Britain. The government considered it of paramount importance to preserve the remaining uncommitted countries, Denmark and Portugal, and especially their navies, from Napoleon's control, and it was Canning who effectively directed the measures it took to achieve these ends. A large fleet and an expeditionary force were sent to back up the demand of an envoy, Francis Jackson, that the prince regent of Denmark should accept an alliance with Britain and hand over his navy to Britain for the duration of the war. When he refused Jackson's demand, which was presented with much less diplomacy than Canning had intended, Copenhagen was bombarded and Zealand invaded, and the Danish fleet was duly seized.

Canning defended his high-handed policy triumphantly in a series of Commons speeches in February and March 1807: ‘he leaped about,’ said Sydney Smith, ‘touched facts with his wand, turned yes into no, and no into yes’ (‘Peter Plymley's letters’, Works, 3 vols., 1848, 3.113n.). Canning's admirers, then and since, have seen this as one of his greatest achievements. Temperley claimed that it

at least kept the seas of England inviolate and the shores of Ireland uninvaded. It averted the threatened closure of the Sound and enabled English troops to be sent to reinforce Sweden. … The presence of the British fleet in the Baltic at least induced the Tsar to suspend his adoption of the Continental system, and his declaration of war until the extreme close of the year 1807. (Temperley, Life, 78–9)

Schroeder, Canning's most recent and most powerful critic, focusing on Canning's ulterior aims, namely to give Russia pause and to strengthen the resolve of Sweden, declares that the expedition was ‘if a crime, even more a blunder’. Zealand had to be abandoned almost as soon as occupied; Russia's declaration of war was ‘speeded up’ by the attack on Copenhagen, and a follow-up expedition to Sweden in 1808 had to be withdrawn. But Schroeder has to admit that the seizure of the Danish fleet was a success of some importance, which contrasted with the contemporary failure of three expeditions promoted by the Grenville ministry to Buenos Aires, the Dardanelles, and Egypt.

To secure Portugal and her fleet Canning signed a treaty with her ambassador on 22 October, under which the regent would leave Europe and establish himself in Brazil. When the regent hesitated to ratify the treaty, Canning ordered a blockade which forced him to comply. The Portuguese navy was seized just as a French army entered Lisbon. As in the Danish case, what followed was less successful. A Spanish rebellion against French influence greatly excited British public opinion, and a force initially under Sir Arthur Wellesley was dispatched to Portugal to assist it. After he had won a battle at Vimeiro, he agreed to an armistice which was followed by the convention of Cintra, the terms of which were negotiated by a commander placed over him and were considered in Britain to have turned victory into humiliation. Canning acquiesced in most of them but with obvious chagrin, blaming Castlereagh as secretary for war for not having disavowed the convention from the start. Another attempt to assist the Spaniards ended early in 1809 with the retreat of Sir John Moore to Corunna. In this case Canning had not only to defend a general in whom he had never felt confidence but also to criticize his friend Frere, whom he had sent as British representative to the rebel government.

Canning was now thoroughly frustrated with the divided conduct of the war. In March 1809 he told Portland that he would resign if the government were not strengthened—by which he meant, first and foremost, removing Castlereagh from the War Office. By May the prime minister, the king, Lord Eldon, and Castlereagh's uncle, Lord Camden, were all working on the assumption that Castlereagh would be moved and were busy devising schemes to achieve this by reshuffling the cabinet. George III authorized Camden to break the news to Castlereagh, but he kept on finding he could not bring himself to do it. Late in July Portland screwed himself up to tell Castlereagh but, before he could do so, had an epileptic fit and the issue became subsumed into the wider question of who should replace Portland as prime minister. Negotiations continued for two more months. Canning said that the choice lay between him and Perceval, and that he would not serve under Perceval. By early September Canning had offered to resign four more times since March. He shocked George III on 12 September by baldly telling him, unasked, that he was ready to form a government. But Castlereagh had at last discovered what had been going on and put the blame on Canning for what seemed like a long course of duplicity. He sent Canning a challenge to a duel. Canning, though he had asked for Castlereagh's removal, had certainly not been responsible for the shilly-shallying of Camden and Portland. But he felt he had to accept the challenge, despite having never fired a pistol in his life. He made his will and wrote a touching farewell letter to his wife. The duel was fought on Putney Heath on 21 September: Canning was wounded but survived. Those in the know criticized Castlereagh for unreasonable overreaction, but the fault was very generally believed to lie with Canning. An immediate result was the appointment of Perceval as prime minister, with neither Canning nor Castlereagh in the cabinet. Even apart from the tragicomedy of the Castlereagh business, Canning had overplayed his hand. He obviously believed, as others like Portland and Perceval often said, that the ministry could not manage the Commons without him. He arrogantly supposed that he alone could give the war coherent and effective direction, and he certainly had exceptional energy, a grand strategic vision, and the ability to appeal to the house and the country. ‘Canning's failure to produce any other convincing reason for his resignation suggests that a bid for power was the real reason’, and he made it far too blatantly. Lord Eldon angrily described him as ‘vanity in human form’ (Hinde, 230–31).

Canning had met Sir Walter Scott in 1806, and two years later, with George Ellis, they founded, as a rival to the Edinburgh Review, the Quarterly Review, the editor of which was William Gifford of The Anti-Jacobin. It became for over a century the semi-official organ of central toryism. Canning seems to have written little for it but he took a continuing and constructive interest in it, and no other minister could have made this important contribution to the development of the party. In the early months of 1809 he purchased Gloucester Lodge, Old Brompton, with the idea of re-establishing his family in the London area.

Out of office, 1809–1816, and MP for Liverpool

For the next three years Canning was in the wilderness, but giving the government general and valued support in the Commons. George III's insanity recurred late in 1810, and early in the following year the prince of Wales became regent. Though he did not, as expected, put the whigs in power, he kept on trying to find ways of ‘strengthening’ his ministry. A by-product of these negotiations was that Wellesley, who had become foreign secretary in December 1809, resigned in February 1812. To Canning's mortification, it was Castlereagh whom Perceval appointed to succeed him. The assassination of the prime minister on 11 May 1812 gave Canning, who had been toying with opposition, another chance of major office. Jenkinson, who had succeeded his father as Lord Liverpool, was eventually confirmed as prime minister, and in July set about capturing Canning. He promoted a reconciliation between him and Castlereagh, who offered to surrender the Foreign Office but insisted on retaining the leadership of the House of Commons. Canning, egged on by his friends, rejected the offer as humiliating. He had overreached himself again.

A general election was called at the end of 1812 in which Canning stood and was elected for Liverpool, free of expense. This was a landmark in his career and in the history of his party. Liverpool, one of the burgeoning cities of the industrial revolution, built on the Atlantic trade, had one of the largest electorates in the country, over 4000. Although the Anglican corporation exercised much influence in elections, this was one of the very few constituencies in the country where new commercial and industrial wealth could assert itself. The town's economy was seriously affected by the war and the orders in council, measures taken while Canning was in office to counter Napoleon's Continental System. The whigs had procured the nomination of Brougham, who had been waging an effective campaign against them outside as well as inside parliament. The tories, led by John Gladstone, father of the prime minister, wanted a plausible alternative candidate. They found one in Canning, whose eloquence and political standing would ensure that the interests of the borough were adequately represented in the Commons without committing it to whiggism. He repeatedly told them that he would not support parliamentary reform and that he favoured Catholic emancipation, which was an unpopular cause in Liverpool; and he defended the orders in council as necessary to the prosecution of the war.

Canning had always believed that the tories need not surrender the media to the whigs. He had shown in The Anti-Jacobin and the Quarterly Review that the press could be used on the side of toryism. He now accepted the challenge of campaigning and appealing by his speeches to opinion in a popular constituency and beyond, something that almost no established politician except Fox—and particularly no tory—had ever attempted. By whatever combination of corruption and conviction, Canning came top of the poll. He then had to attend numerous celebratory dinners in Liverpool, and also in Manchester, where he forcefully defended the system that denied the place representation. In Liverpool a Canning Club was founded in 1812. He told his mother:

it certainly has been gratifying, and glorious beyond my most sanguine dreams of popular ambition. I may have looked to be a Minister—but I hardly ever thought that it would have fallen in my way to come in so close contact with so large a portion of the people, and to be so received. (Hinde, 262)

Liverpool was an extremely demanding seat. His constituents supplied an office and a secretary but expected him to consult them, act for them, and report to them. He pleased them by voting for the end of the East India Company's trade monopoly in 1813. He retained the seat at a by-election in 1816 and the two general elections of 1818 and 1820, but gave it up in 1822, to be succeeded as MP by William Huskisson, by then his principal lieutenant.

Despite his election victory of 1812, at Westminster Canning's situation was dismal. He felt so dispirited that he officially dissolved his little parliamentary party, as its members, he thought, were suffering by their devotion to him. His attendance at Westminster became less regular. He wrote to Leveson-Gower on 22 October 1813:

At present …—while the station in Europe and in history, which I have thrown away, is full before my eyes; while I am alive to the sense of conscious ridicule (to say nothing of the sense of public duty) as having refused the management of the mightiest scheme of politics which this country ever engaged in … from a miserable point of etiquette—one absolutely unintelligible … at a distance of more than six miles from Palace Yard—I really think I am much better at home. (Hinde, 267)

In the summer of 1814 Lord Liverpool made him an offer which both pandered to these feelings and made it easier for him to take his invalid son to a better climate. The Canningites would become avowed supporters of the government; Liverpool would give ministerial posts to Huskisson and Sturges Bourne, a viscountcy to Leveson-Gower, and an earldom to Boringdon; and Canning himself would be sent to Lisbon, in ‘a great, splendid anomalous situation wholly out of the line of ordinary missions’ (ibid., 269), at a salary of £14,000 p.a., to receive the regent of Portugal back from Brazil. Canning accepted, and sailed from Portsmouth in November, to the accompaniment of accusations of jobbery from the whigs. The embassy proved a serious task, since the regent did not return and Canning had difficult dealings with his council, especially when they felt threatened by Napoleon's Hundred Days. After Waterloo the mission was terminated, but Canning and his family remained abroad. He thus took no part at all in the peacemaking of 1814–15 or in the cabinet and public discussions about it.

India and the queen's affair, 1816–1822

While still in Portugal, in March 1816, Canning was offered by Liverpool, and accepted, the comparatively humble post of president of the Board of Control within the cabinet. In this post his main contribution was to give distinctly limited support and reluctant approval to the remarkably successful campaigns of the governor-general, Moira, against the Pindaris and the Marathas, which greatly extended the area of central India under British control. In parliament and outside he powerfully defended the government's measures of 1817 and 1819 (Six Acts) to curb domestic unrest. In speeches in Lancashire, as well as in the Commons, he strongly supported the magistrates' actions at Peterloo, playing on the fears of sober citizens for their property and security. However, his position in the cabinet did not give him much influence on general issues, except perhaps on foreign policy. He opposed, with little immediate result, Castlereagh's ‘very questionable policy’ of agreeing to regular meetings with ‘despotic allies’ (Thorne, 401; Temperley, Foreign Policy, 43–4). But ministers' attitudes were shifting, as was clearly shown in the classic state paper of 1820, in which Castlereagh declared emphatically that Britain's policy was non-intervention in the affairs of other states. This document certainly owed something to Canning's advocacy and drafting.

The accession of George IV in 1820 made the position of his queen the great issue of politics, putting Canning in special difficulty because he had been her friend—even if not, as the king believed, her lover. When she arrived in England in June Canning offered to resign, but was persuaded to stay on. Though he supported the government's policy, he infuriated George by expressing sympathy for her in the Commons. He rode out numerous royal tantrums but decided on 12 December 1820 that he must resign, ostensibly because he did not approve of her being treated as a guilty party. Since it seemed he could never hope to achieve his ambition of succeeding Castlereagh as foreign secretary and leader of the house, he had asked Liverpool early in 1820 for the succession to Moira as governor-general of Bengal. A spell in that post would restore his precarious financial position: much of his wife's fortune had been either spent or invested in a Lincolnshire estate that produced only a low return; without a ministerial salary his annual income was only £2200. In 1821–2 Liverpool tried strenuously to persuade the king to allow him back into the cabinet, but George obstinately refused to have him, and the prime minister concluded that the only way in which the ministry could avoid ‘the greatest inconvenience’ from his presence in the Commons would be to dispatch him to India. In March 1822 he accepted the governor-generalship. In May, believing that this would be his last opportunity, he obtained a majority in the Commons for a symbolic measure of Catholic emancipation, allowing Catholic peers to take their seats, but the Lords rejected the bill.

Foreign secretary, 1822–1827

On 12 August Canning's career was transformed by another stroke of fate: Castlereagh committed suicide. It was universally expected that Canning would succeed him, but the prime minister met intransigent opposition to this proposal from the king. Meanwhile Canning continued his preparations to go to India and went off to a round of farewell dinners and speeches at Liverpool. George IV gave way only after all members of the cabinet, including Peel and Wellington and the other opponents of Catholic emancipation, declared that Canning's appointment was necessary to the government's position in the Commons. At last, on 9 September, Liverpool was able to offer Canning the foreign secretaryship and the lead in the Commons, and on the 13th he accepted. He was elected for the government borough of Harwich early in 1823.

Canning's accession was the most conspicuous of a series of ministerial changes during the years 1821–3 which made Liverpool's government seem ‘new’, ‘liberal’, and ‘popular’. Foreign affairs were the main business of governments in the days before parliamentary reform, and the issues with which he had to deal greatly excited the public. The force of his oratory and the vigour and mastery of his dispatches, which he made a point of publishing much more freely than any of his predecessors, ensured that he cut an exceptional figure as foreign secretary both at home and abroad; and it was he and his foreign policy that were generally taken to embody the new attitude of the government.

The congress of Verona met in October 1822 and found itself unexpectedly concerned with possible intervention by the allied great powers to quell a revolt in Spain. Canning instructed Wellington, the British representative, to oppose such intervention, and in this succeeded. At the opening of parliament on 4 February 1823 the speech from the throne, opposing all intervention, was so well received that the opposition moved no amendment to the address. However France, with Chateaubriand as chief minister, was anxious to intervene on her own account, and this Canning could not prevent. After the French invasion in April, Canning made a powerful speech hostile to France and sympathetic to Spain, announcing that Britain would be neutral and publishing a large selection of diplomatic correspondence to justify his policy. When he came to answer his critics, he called himself ‘an enthusiast for national independence’, but stressed the blessings that Britain derived from remaining at peace. He won the vote by 372 to 20. In October he defended his policy in a great speech at Plymouth, where he was receiving the freedom of the borough.

Through most of Canning's period as foreign secretary, it was a major question whether to recognize the Latin American republics that had rebelled against Spain. Although Castlereagh had accepted that recognition was only a matter of time, the king and Wellington were violently opposed to it. They were infuriated by Canning's appeals to public opinion and his avowed sympathy with nationalist feeling, and they intrigued with foreign diplomats and tory dissidents against him. It was only with the strong support of Liverpool, and by threatening to resign and inform the public about the king's machinations, that Canning obtained the recognition of Buenos Aires in August 1824, and Colombia and Mexico early in 1825. ‘Behold,’ he wrote, ‘the New World established, and if we do not throw it away, ours’ (Hinde 372). Once he had carried these points, the king abandoned his long-standing vendetta against him, became almost his ally, and took to showing him the diplomatic correspondence he received as king of Hanover.

Canning's old involvement with Portugal was revived. The regent had actually returned to Lisbon in 1821 and accepted a constitutional regime, but it was overthrown two years later. In order to restore something like it and to maintain British influence in Portugal, Canning ordered intervention by the British navy, which he claimed was different in principle from intervention by an army. A pro-British regime was established early in 1825, and soon afterwards a British representative negotiated the recognition by Portugal (and Britain) of Brazilian independence. At the end of 1826, however, an invasion of Portugal from Spain led to Canning's proposing, and the Commons' enthusiastically supporting, the dispatch of a military expedition to preserve her liberties—intervention which he claimed was justified because it was designed to defeat the intervention of other powers and thereby to preserve the principle of non-intervention.

Canning's other main preoccupation in foreign policy was the Eastern question, especially as it was affected by the Greek revolt against Turkey in 1821, with which Russia sympathized. He recognized the rebels as belligerents in 1823 on purely pragmatic grounds, insisting that Britain remain completely neutral. He evaded attending an international congress on the issue desired by Tsar Alexander, but he sent Wellington to St Petersburg to try to get an agreement with the new Tsar Nicholas. On 4 April 1826 Wellington signed there a protocol declaring that, subject to Turkish agreement which Canning believed could be obtained, the Greeks would receive a measure of autonomy. In July 1827 England, Russia, and France signed the treaty of London intended to implement this protocol. At Canning's death the question was unresolved, but when the allied fleet, exceeding its instructions, destroyed the Turkish navy at the battle of Navarino on 20 October, Greek independence was secured. Canning received much of the credit for it from liberals, and corresponding blame from the tory ultras.

It is Canning's foreign policy from 1822 to 1827 on which his reputation mainly depends. The business of the Foreign Office vastly increased in these years, and his capacity for work—in particular his ability to reel off with amazing rapidity beautifully phrased and argued dispatches—was the admiration of his staff. It is symbolic that he, alone of foreign secretaries, actually took up residence at the Foreign Office in 1825, having sold Gloucester Lodge. Temperley, his greatest admirer, characterized his policy as:

non-intervention; no European police system; every nation for itself, and God for us all; balance of power; respect for facts, not for abstract theories; respect for treaty rights, but caution in extending them … a republic is as good a member of the comity of nations as a monarch. ‘England not Europe.’ ‘Our foreign policy cannot be conducted against the will of the nation.’ ‘Europe's domain extends to the shores of the Atlantic, England's begins there.’ (Temperley, Foreign Policy, 470–71)

Canning's conduct of foreign policy was often taken as a touchstone by Victorian politicians, and Palmerston declared himself his disciple.

The major criticisms levelled at Canning's policy are of two kinds. First, it has been maintained that it differed from Castlereagh's in style rather than in substance. That their styles were widely different cannot be questioned: Castlereagh's prose was notoriously awkward, whereas Canning's speeches and dispatches were eloquent and ruthlessly clear, though not always tactful; and his appeal to public opinion in speeches both inside and outside the Commons, and by the publication of dispatches, was unprecedented. He claimed to rest his policy on Castlereagh's state paper of 1820; and, if the thinking behind that document was genuinely Castlereagh's, then he anticipated much of Canning's policy. But contemporary ultras, liberals, and radicals were united in their conviction that it was novel. ‘A malevolent meteor’, Metternich described him, ‘a revolution in himself alone’ (Hinde, 462). The second main line of criticism rules out the first. This view, expressed most ably by Schroeder, is that Canning's policy was utterly and deplorably different from Castlereagh's, in that it abandoned the beneficent new system established at Vienna to maintain the peace of Europe, and substituted an ultimately irresponsible dedication to British interests narrowly conceived. It is further suggested that Canning tuned his foreign policy to procure himself applause and serve his domestic political ambitions. He certainly wrote flippant dispatches—one of them, famously, in rhyme—to the rather too numerous friends for whom he had found diplomatic posts. But it is very questionable that his foreign policy, bitterly contested as it was by the king, ministers, and many of his own party, was calculated to advance his domestic career. And the essential difficulty about Schroeder's view is that it is impossible to imagine the European rulers of the nineteenth century, particularly those of Austria, adapting themselves in a series of congresses to the economic, social, political, and intellectual developments of the age.

Prime minister, April–August 1827

Like his predecessor, Canning was terribly overworked through being leader of the Commons as well as foreign secretary. As leader he had, of course, to master many subjects. None moved him or troubled him more than Catholic emancipation, which he wished to promote but which continued to be the subject of bitter division within his own party. ‘Consider a little’, he wrote in 1825, when he was trying to carry a limited measure of emancipation,

what it is to go into the House, as I did on Monday at five in the afternoon, remain there till two in the morning; then to have for sleep, refreshment, and such business as will not stand still, only twelve hours; then a Cabinet from two to four, then to be in the House again from five to nine, to get up to speak for two hours at eleven, and to get to bed not before five. (Hinde, 398)

On economic and fiscal policy Canning was less well informed and less dogmatic than Liverpool, Peel, and Huskisson, but he backed the reformers, helped to argue their economic measures through the house, and became identified with them. On the mitigation of the corn laws he was more personally engaged, and a speech he made on the subject in 1825 infuriated the tory ultras. He argued for taking account of ‘the progress of political knowledge’, adding: ‘those who resist indiscriminately all improvement as innovation, may find themselves compelled at last to submit to innovations, although they are not improvements’ (Hinde, 403). His stance on these matters, as on foreign policy, was more agreeable to the opposition than to many tories.

At the general election of 1826, in which Canning was returned for Newport, Isle of Wight, the divisions within the government on the Catholic question and the corn laws were only too obvious, and the results suggested that English opinion was hostile to emancipation. Liverpool was growing increasingly despondent about keeping the cabinet together when he had an incapacitating stroke on 17 February 1827. Most people assumed that Canning would succeed him and, after a lengthy delay during which other possibilities were canvassed, the king appointed him prime minister on 12 April. But Wellington and his friends had become so jaundiced about Canning's foreign policy, his ‘Catholic’ and ‘liberal’ sympathies, his ambition, his intellectual arrogance, and what they saw as his untrustworthiness that they refused to serve under an avowedly ‘Catholic’ premier. The king was furious with them and took up Canning's challenge: ‘Sir, your father broke the domination of the Whigs. I hope Your Majesty will not endure that of the Tories’ (Hinde, 443). Canning managed to persuade a few minor ‘protestants’ to stay on, but made up his cabinet largely from liberal tories and, after protracted negotiations, a contingent of moderate whigs led by the marquess of Lansdowne. All had to agree not to propose either parliamentary reform or the repeal of the Test Act. Among tories Robinson became Viscount Goderich and secretary for war and the colonies, and Huskisson president of the Board of Trade; Lord Dudley became foreign secretary, and initially Sturges Bourne was made home secretary, and Canning's brother-in-law, the duke of Portland, lord privy seal. All these were undoubted Canningites and the last three quite untried in office. Lord Palmerston, who had languished in minor office since 1809, entered the cabinet, and Canning himself took the chancellorship of the exchequer. William Lamb was made Irish secretary. When Lansdowne joined the cabinet in May he took no portfolio, but two months later he became home secretary and Carlisle, another crony of Canning's, lord privy seal, while Sturges Bourne and Portland were relegated to lesser roles. Brougham and many whigs sat on the government side of the house, and Althorp soon joined them in support of ‘a government actuated by liberal and enlightened principles’ (ibid., 453). Canning had to give up his parliamentary seat when made first lord of the Treasury, and was returned at a by-election for Seaford.

The ministry found its position in the Commons difficult, and in the strongly tory Lords almost impossible. It failed to get through a modification of the corn laws. Canning was subjected to personal attacks of unusual violence. A month after his mother's death and a week after Canning had taken office as prime minister Grey, who had always disliked him, declared in the Lords that he was disqualified for the post because his mother had been an actress; and the tory ultras denounced him for having allegedly betrayed his tory principles and friends. But the government's greatest weakness was Canning's health. For some years he had been suffering ever more frequently from prostrating attacks of what was called gout. It was clear to everyone that he was under enormous strain. He had caught a chill, like several other ministers, while waiting two hours in St George's Chapel, Windsor, for the funeral of the duke of York on 5 January, and never fully recovered. He got worse in July, when the duke of Devonshire lent him Chiswick House to give him some respite. On 30 July he told the king that he did not know what was wrong with him but he was ill all over. Doctors said he was suffering from an inflammation of the liver and the lungs. He died at Chiswick, in the room in which Fox had died, on 8 August.

The coalition ministry was continued under Goderich as prime minister but lasted only until January 1828. Its significance was not in its achievement but in its formation and composition. Although the more rigorous whigs, especially Grey, had refused to serve, the cabinet anticipated the reforming ministry that he was to create in 1830: it was the bridge over which Robinson, Palmerston, and other liberal tories passed to become parliamentary reformers. The refusal of office by Wellington and Peel marked the decisive split between them and the liberal tories, despite a brief reunion in the early stages of Wellington's administration of 1828. In his youth Canning had been part of the movement of the whigs into coalition with Pitt against the threat of the French Revolution. Now he was part creator and part victim of the movement of public opinion in the country and in parliament away from the paranoiac fear of change at home and abroad which the French Revolution and Napoleon had induced: victim both because in emphasizing the liberal elements of Pitt's heritage he lost his natural support across the tory party, and because he was so virulently attacked for it. The scenario was never forgotten by those who had observed it. When on 8 June 1846 Lord George Bentinck, Canning's nephew and private secretary, denounced Peel's proposal to repeal the corn laws, his backers flung against Peel the taunt: ‘Who killed Mr Canning?’ In 1886 Gladstone said of Canning, who remained always one of his heroes, that he had ‘emancipated this country from its servitude to the Holy Alliance; and for so doing he was more detested by the upper classes of this country than any man has been during the present century’ (H. C. G. Matthew, Gladstone, 1875–1898, 1995, 97).

Canning's death produced an outpouring of sympathy from press and public. It was emphasized that he was one of the people, untitled, without inherited wealth and connections, who had made his way to the top by his own ability and exertions. His early childhood had been passed in by far the poorest, and socially the most dubious, circumstances of any man who achieved major political office before the appointment of the first Labour cabinet in 1924; and he remained the only man without a title to have become foreign secretary until Ramsay MacDonald took the office. He received a public funeral and was buried in Westminster Abbey on 16 August, close to Pitt. His wife, Joan, lived until 1837, jealously defending his political record. She was created a viscountess in 1828, when parliament granted an annual pension of £3000 to the Canning family. Canning was survived by two sons, William Pitt (1802–1828), who was a naval officer and drowned at an early age, and Charles John Canning (1812–1862), who became governor-general of India. His daughter, Harriet (1801–1876), married Ulick John de Burgh, the first marquess of Clanricarde (1802–1874).

Estimate

Canning was one of the handful of men who have brought transcendent talents to the practice of politics in Britain. His contemporaries all recognized him as a man of outstanding ability and personality, about whom it was impossible to be neutral. His gifts were limited in scope: though he was a steadfast supporter of the Church of England, he was uninterested in theology; he confessed to being wholly unmusical; and he took no part in sport of any kind. His recreations were conversation, literature, playgoing, and, when it became possible after the war, continental travel. His knowledge of the classics was recognized as exceptional. He was a fluent and witty versifier, and his wicked parodies of Southey, which led to the withdrawal of the originals, hold their place in modern collections. His and George Ellis's take-off of contemporary German drama, The Rovers, was performed at the Haymarket in 1811.

As a minister Canning was formidably hard-working. But his greatest skill and weapon was his style, as expressed in his dispatches but most notably in his speeches. Time and again his oratory saved the day for himself and his colleagues in the Commons, and after 1812 it won him a unique reputation in the country. Among the elaborate images for which he was notorious the following, from a speech at Liverpool on 30 August 1822, a fortnight before he became foreign secretary for the second time, was perhaps the most striking and characteristic:

What should we think of that philosopher, who, in writing, at the present day, a treatise upon naval architecture and the theory of navigation, should omit wholly from his calculations that new and mighty power … which walks the water, like a giant rejoicing in his course;—stemming alike the tempest and the tide;—accelerating intercourse, shortening distances;—creating, as it were, unexpected neighbourhoods, and new combinations of social and commercial relation;—and giving to the fickleness of winds and faithlessness of waves the certainty and steadiness of a highway upon the land? … the power of STEAM. … So, in political science, he who, speculating on the British Constitution, should content himself with marking the distribution of acknowledged technical powers between the House of Lords, the House of Commons, and the Crown, and assigning to each their separate provinces, … and should think that he had thus described the British Constitution as it acts and as it is influenced in its action; but should omit from his enumeration that mighty power of Public Opinion, embodied in a Free Press, which pervades, and checks, and perhaps, in the last resort, nearly governs the whole;—such a man would, surely, give but an imperfect view of the government of England as it now is. (Therry, Speeches, 6.404–05)

Only Canning, among the politicians of his time, offered the proof that in the unreformed system a man of the people could reach the summit of politics, and that public opinion could be effectively mobilized in support, first, of reaction against the French Revolution, and then of a liberal tory government opposed to parliamentary reform.

Derek Beales DNB

Sir Thomas Lawrence, (1769–1830), painter and draughtsman, chiefly of portraits, was born on 13 April 1769 at 6 Redcross Street, Bristol, the youngest of the five surviving children of Thomas Lawrence (1725–1797), then a supervisor of excise, and Lucy (1731?–1797), younger daughter of the Revd William Read and his wife, Sarah, née Hill. Through her father Lucy Lawrence was related to the Read family of Brocket Hall, Hertfordshire, and she had connections through her mother with other county families. As many as perhaps eleven other children were born to her between 1754 and 1772, but all died in infancy.

To a most unusual degree, childhood and early activity were synonymous in the life of Lawrence. His father moved from Bristol to Devizes in 1773, becoming landlord of the Black Bear, a well-known coaching inn of the London–Bath road. Within two or three years the very young Lawrence had revealed his talent for drawing, being capable particularly of sketching, in pencil, likenesses of people.

Visitors to Lawrence's father's inn included numerous social and cultural personalities, and the boy was much noticed by them—for his own sake and through the efforts of his proud, pretentious, and probably over-persistent father. Profile portraits in pencil of Lord and Lady Kenyon, who stayed at the Black Bear in 1779, document Lawrence's ability at that date (1779; priv. coll.). He would remain continuously at work as an artist for the subsequent fifty years, until the day before he died.

The boy Lawrence was early noticed, additionally, because of his handsome appearance and his gift for reciting verse, from Shakespeare and Milton. Fanny Burney recorded in April 1780 that she had found at the inn ‘a most lovely boy of ten years of age’ (Diary and Letters, 1.304), who possessed an astonishing skill in drawing. Mrs Lawrence informed her that he had already visited London and been pronounced a genius by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Another, more frequent visitor, David Garrick, seems to have seriously considered that the future career of the boy (not quite ten at Garrick's death) lay between painting and the stage.

Although early and usefully conditioned in social behaviour, with manners that were to be commented on later by contemporaries as extremely, if not excessively, polished, Lawrence received little formal general education. In adulthood, he wrote of his regret that his parents, for all their love, had not provided their son with ‘two or three parts in education of the utmost importance to the future happiness of the man’ (Williams, 2.43). He referred specifically to practical grasp on money matters, but must have intended a wider application.

Lawrence's father was naturally improvident, though naturally optimistic. In 1779 he was declared a bankrupt, and thenceforward his youngest son became the chief financial mainstay of the family. Some sort of promotional tour for him was conceived by Lawrence senior in or about 1780, beginning at Oxford, where his earliest biographer states that he took ‘the likenesses of the most eminent people’ (Williams, 1.67). The episode is obscure, however, since no such portraits have been identified, and the tour may in reality have been something of a failure.

After a short stay at Weymouth, the Lawrence family settled in Alfred Street at Bath. By 1783 Lawrence was practising mainly as a painter of small portraits in pastel, receiving for half-lengths 3 guineas, ‘at that time and for Bath a very extraordinary sum’ (Williams, 1.73). The medium of pastel was one Lawrence ceased to use after approximately 1790, and the majority of surviving pastel portraits from his years at Bath are no more than competent. But the lively, fashionable cultural milieu of the city was to be of great significance in his development, both artistically and emotionally.

Still only in his teens, Lawrence was yet able at Bath to emancipate himself—to some degree—from his father. Among collectors and connoisseurs he found several friendly patrons and admirers who allowed him access to drawings, prints, and other works of art they owned—thus firing him with a passion to collect himself, as well as giving him some contact with the greatest Italian old masters, supremely Michelangelo. Writing to Charles Eastlake in 1822, he described how he had used to copy, ‘Night after Night’, prints after the prophets and sybils of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and he characterized his mind at that period as being ‘however fettered, strongly and singularly excited’ (Layard, 170). One potential patron offered to finance his journey to Italy, though obtuseness or self-interest led his father to refuse. But Lawrence was also made welcome socially, especially in the sympathetic family circle of a local physician, Dr William Falconer; he was probably the first of those older male figures who would become father-surrogates throughout Lawrence's life. And at Bath, Lawrence's enthusiasm for the theatre resulted in his seeing and being fascinated by Mrs Siddons, with whose two elder daughters, Sally and Maria, he was later to be romantically entangled.

Lawrence's artistic education seems to have been no more firmly grounded than was his general education. He passed as self-taught, though at Bath he most probably had some lessons in handling of oil paint from the fashionable elderly portrait painter William Hoare, whose son Prince Hoare remained a supportive friend. It was apparently in 1786 that he painted in oils a large composition of Christ bearing the cross (lost), which is likely to have been copied or derived from William Hoare's painting of the same subject (St Michael with St Paul Church, Bath). A copy made by Lawrence in crayons of Raphael's Transfiguration (Yale U. CBA) gained him the award in 1784 of a silver palette and 5 guineas from the Royal Society of Arts in London. All the evidence suggests that in these years he aspired to a future not merely as a painter of portraits but as an artist in the grand manner. However fruitful Bath had been in his development, it could not compete with all the advantages of London. In 1787 Lawrence left Bath for London and was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools there.

First years in London

In going to London, Lawrence had taken a decisive step. He remained based there for the rest of his life. He moved from a first address at 4 Leicester Square to 41 Jermyn Street, then to 24 Old Bond Street, and next to Greek Street, Soho, where his parents lived with him. He retained the house until he finally settled in a large house at 65 Russell Square (des.), where he lived by himself from 1813 until his death.

Lawrence soon ceased to attend the Academy Schools. His proficiency in drawing was recognized at once as outstripping all his fellow students. He sent several works, in pastel, to the Royal Academy exhibition in 1787, and in 1789 he exhibited a full-length portrait in oils, Lady Cremorne (1788–9; Tate collection) which, despite some stiffness in the pose and face, is remarkable for its bravura passages of paint, especially in the sky and landscape. In a letter written to his mother in Bath, dating from either 1787 or 1788, he made the characteristically hedged yet extraordinarily confident declaration, ‘To any but my own family I certainly should not say this; but excepting Sir Joshua, for the painting of a head, I would risk my reputation with any painter in London’ (Layard, 7–8).

The year 1790 marked full public recognition of Lawrence's achievements, in terms of prestige as well as of art. In that year he exhibited at the Royal Academy twelve portraits, among them two full lengths, the actress Elizabeth Farren (1789–90; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Queen Charlotte (1789–90; National Gallery, London). Reviews of the exhibition warmly praised both paintings, which rank among his finest achievements. Paint is handled with a richness, crispness, and confident pleasure seldom seen in British art, while the likenesses and costumes are seized with equally pleasurable confidence. And complementing the freshness of portrayal is a vivid, fresh response to differing aspects of English landscape.

Lawrence had been bidden to Windsor in September 1789, to paint the queen and also Princess Amelia (1789; Royal Collection). Although the queen's portrait was not acquired by the king, Lawrence at twenty had received his first important royal patronage. Gainsborough was dead, and Lawrence was widely recognized as the successor to Reynolds, whose health and art were in decline. George III pressed the Royal Academy to elect him an associate in 1790, but it refused because of the regulation against election of associates aged under twenty-four. However, it elected him the following year. When Reynolds died in 1792, the king appointed him painter-in-ordinary. In 1794, at the earliest permitted age of twenty-five, he was elected a full academician.

During the 1790s Lawrence seems to have believed that he could combine activity as a portrait painter with producing occasional history paintings. At the Royal Academy in 1791 he exhibited, as well as several portraits, a small history painting, Homer Reciting his Poems (1790; Tate collection), a composition commissioned by the antiquarian scholar and connoisseur Richard Payne Knight. The effect is of a pastoral landscape, attractive but hardly ambitious, nor particularly classical in mood. More interesting may have been the Shakespearian subject Prospero Raising the Storm (exh. RA, 1793), a large canvas he is said to have later utilized for the portrait of John Philip Kemble as Rolla (1800; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, USA).

In 1797 Lawrence exhibited his most ambitious attempt at a history picture, turning back for inspiration to Milton's Paradise Lost, the poem which had been a source for recitation and delineation by him from his boyhood. The huge canvas of Satan Summoning his Legions (1796–7; RA) was his final effort to create a grand historical composition. It was very unfavourably received, but Lawrence himself defiantly continued to esteem it. After seeing it again in 1811, he wrote despondently of experiencing a sense of ‘the past dreadful waste of time and improvidence of my Life and Talent’ (Layard, 84). Darkened though the painting now is, and extremely difficult to assess, it is by no means unimpressive, for all the old master echoes and its debt to the style of Fuseli.

The 1790s proved testing for Lawrence in numerous ways. In 1797 first his mother and then his father died, and between the two deaths he reflected ruefully on the differences of character and disposition separating himself from his ‘essentially worthy’ father, concluding, ‘To be the entire happiness of his children is perhaps the lot of no parent’ (Williams, 1.186). Later in the same decade he conducted a highly charged, frustrated love affair involving both Sally and Maria Siddons, and profoundly perturbing Mrs Siddons. Maria died in 1798, and Sally in 1803. Like his two brothers, Lawrence was never to marry.

From very early on in his London years Lawrence established links of unfailing friendship with the interrelated families of William Lock, of Norbury Park, Surrey, and John Julius Angerstein, of Woodlands, Blackheath, Kent. Both were collectors and became his patrons, and through Angerstein's stepdaughter, the wife of Ayscoghe Boucherett MP, he became friendly also with the Boucherett family of North Willingham, Lincolnshire. As well as painting portraits of various members of these families, he made several tender and charmingly informal drawings of the children and of the mothers, for example, Amelia Angerstein, née Lock, nursing a baby (inscribed ‘Willingham 1810’; priv. coll.). The most important of all friendships was the one that he early established with the much older fellow artist Joseph Farington, who advised and guided him until the latter's death in 1821. Farington's now fully published Diary provides a mass of information about Lawrence's personal, financial, and artistic affairs but attempts no overall view of the man.

The opening years of the nineteenth century

The first years of the new century were probably the most difficult and stressful in Lawrence's life and career. In 1801 he wrote privately to Mrs Boucherett of feeling ‘shackled into this dry mill-horse business’ of painting portraits, which must yet be gone through, ‘with steady industry’ (Williams, 1.222). A sense of being thus ‘shackled’ seems to have continued to haunt him. And in the same letter, with accidental accuracy, he assumed that half his life was already over.

Lawrence's debts became a crippling burden from which he never escaped. He had been generous with financial help to his family, and would always be so to other, often younger, artists. He spent large sums on artistic materials, as well as on adding drawings to his collection. Contemporary rumours of his gambling, or even of being blackmailed, appear groundless; and it seems much more likely that his temperament and upbringing united to leave him bewildered or bored by the demands of prosaic daily existence.

By 1807 Lawrence's affairs had fallen into the gravest confusion. He owed more than £20,000. For Farington he drew up a detailed estimate of work to be done and moneys to be earned, with highly optimistic totals inserted, implying almost unceasing labour. Farington responded prudently by advising him to consult the well-disposed banker Thomas Coutts, providing him with an explicit statement of all debts, and warning him against presuming on too large an income until ‘you have worked off much of the heavy load of unfinished pictures’ (Layard, 54–5). Work though he did, that was a goal Lawrence would never achieve.

During these years Lawrence's art revealed virtually nothing of his private difficulties. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Royal Academy, with portraits which were often rightly hailed as remarkable for their originality as well as for their sheer accomplishment. It seems clear that the prospect of public exhibition, with the concomitant requirement to meet a fixed date, acted upon him as a necessary and almost essential spur.

Many commissions remained unfinished, and patrons complained bitterly. But Lawrence could produce portraits which ranged from agreeable presentation of well-bred children and fashionable women to such a tough, characterful depiction as Lord Thurlow (1802–3; Royal Collection), exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1803 to a chorus of praise. In 1806 he contributed a bravura variation of the mother and child theme in a large, richly coloured portrait, in tondo format, of the duke of Abercorn's mistress, with her son, tactfully entitled A Fancy Group (1805; priv. coll.). In the following year his chief exhibit was a group portrait, at once dignified yet animated, of the financier Sir Francis Baring with his brother, John, and son-in-law, Charles Wall (1806–7; priv. coll.). It too was well received, though Lawrence was piqued by comments in the Morning Chronicle, whose editor, James Perry, championed the rival portraitist John Hoppner.

Hoppner was patronized by the most fashionable and influential figure in society, the prince of Wales, who did not employ Lawrence at that period. The prince's near-ostracism of Lawrence probably arose not only from opposition to those favoured by his father but because Lawrence had been patronized by the princess of Wales, Caroline of Brunswick. At the Royal Academy in 1802 he showed a somewhat hectic full length of her with her daughter, Princess Charlotte, (1801–2; Royal Collection), and his own conduct in connection with the princess came under review in the ‘delicate investigation’ of 1806. While entirely cleared of any impropriety, he is likely to have appeared tainted in the prince's eyes simply by association with his estranged wife.

The not unexpected death of Hoppner in January 1810 removed Lawrence's chief competitor, leaving him conscious that their long, acrimonious rivalry had ended without any reconciliation. It must be more than coincidence that in the same year he raised the prices of his portraits, from 200 guineas to 400 guineas for a full length.

The pattern of Lawrence's existence was apparently set. He painted unremittingly, seldom entertained, and tended to prefer a modest social life spent in the company of ungrand, sometimes unmarried female friends. Some kind of amitié amoureuse seems to have developed between him and Mrs Isabella Wolff, née Hutchinson, who separated from her husband, Jens Wolff, the Danish consul in London, about 1810. Lawrence had begun a beautiful, profoundly meditated portrait of her in pensive mood several years before, but finished it only years later, for the Royal Academy exhibition of 1815 (c.1803–1814/15; Art Institute of Chicago). Until her death in 1829 she was probably the most important person in his emotional life.

The regent's patronage and travel abroad

In or about 1810 Major-General the Hon. Charles Stewart, Lord Castlereagh's half-brother and later third marquess of Londonderry, sat to Lawrence for the first time. The resulting portrait (not certainly identifiable) was exhibited at the Royal Academy in the following year. More important than the painting was the unexpected friendship which quickly sprang up between the painter and the aristocratic soldier-cum-diplomat, nine years his junior. Lawrence would greatly benefit from being under Stewart's aegis abroad, and characterized him later as ‘one of the most zealous friends that ever man had’ (Williams, 2.463).