Christies stencil on the reverse "379HN"

Lt William Lewis Clinton- Baker, R.N

Lot 107, 1st June 1945, Christies, Bt Bangal, sold for £27.6.0

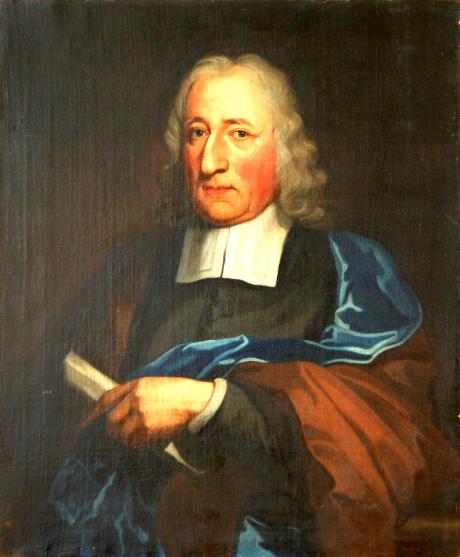

John Swynfen or Swinfen was commonly called "Russet Coat", from his affected plainness of dress. His portrait shows him in Puritan dress with a blue silk lined russet cloak. Although Puritan in dress his extravigant cloak was presumably worn for this portrait ! Swynfen [Swinfen], John (1613–1694), politician, was born at Swynfen Hall, Weeford, in south-east Staffordshire, on 19 March 1613 and was baptized there, at St Mary's, on 28 March, the eldest son of Richard Swynfen (bap. 1596, d. 1659), landowner, and his wife, Joan (bap.

1591, d. 1658), daughter of George Curitall, alias Harman, of Lichfield. Swynfen enrolled at Pembroke College, Cambridge, in autumn

1628 and obtained his BA four years later. He returned to the ancestral home in the tiny hamlet of Swynfen and in Weeford church on

26 July 1632 married Anne (bap. 1613, d. 1690), daughter of a neighbouring gentleman, John Brandreth. Anne proved ‘an inestimable blessing to her husband’ (Shaw, 2.25) in a union that lasted nearly fifty-eight years and produced six sons, all of whom died before their father, and four daughters.

In the 1640s Swynfen enthusiastically embraced the cause of parliament. He signed a radical petition in favour of parliamentary control of the militia and godly reformation in March 1642; took part in the defence of Lichfield Close against Prince Rupert's forces in April 1643; and was appointed a member of the Staffordshire parliamentary committee in June 1643. As a man who believed in the uncompromising prosecution of the war against the king, Swynfen had a natural affinity with the leader of the militants on the Staffordshire committee, Sir William Brereton, with whom he developed a close partnership, supplying him with intelligence on military, political, and a host of other matters. Swynfen's support for Brereton involved him in the latter's bitter feud with Basil Feilding, second earl of Denbigh. In spring 1645 he furnished evidence against Denbigh in the House of Lords' investigation into the earl's conduct, accusing him of rank disaffection, pusillanimous leadership, and partiality in the treatment of royalist delinquents.

Denbigh retaliated by berating Swynfen's own ‘factious demeanour’

(Parl. Arch., House of Lords MSS, special depositions, 2 May 1645) as well as exposing the blatant favouritism which he had shown to sequestrated cavaliers such as Sir John Skeffington. Despite these allegations, in summer 1645 Swynfen was nominated a Staffordshire JP while in late October he secured election as a recruited MP for the borough of Stafford. His opponents called him ‘Russet-coat, from his affected plainness and pretences to sincerity’ (Shaw, 27), but Brereton, his parliamentary sponsor, declared that he was a ‘very choice, able man’ who would be ‘very serviceable to the Kingdom’

(Letter Books, 2.19), an accurate prediction as Swynfen turned out to be an outstanding MP.

From the outset Swynfen distinguished himself by his devotion to parliamentary business, serving on innumerable committees, and on 3 January 1648 he was rewarded with a prestigious appointment as member of the Derby House committee of both kingdoms. As ‘a rigid Presbyterian’ (Kidson, 29) who had subscribed to the solemn league and covenant and who had been appointed to a select committee for establishing classes and elderships in London peculiars in January 1646, Swynfen naturally opposed the radical religious and political stance of the New Model Army and on 3 August 1647 was one of the three MPs sent on the fruitless exercise of ordering it not to advance on London to intimidate parliament. Swynfen's alienation from the army became even more pronounced after the second civil war, when he threw his weight behind the Long Parliament's last-ditch attempt to reach a settlement with the king. During the negotiations Swynfen's fellow MP John Crewe, who was in direct communication with Charles I, constantly urged him to use his moderating influence in the Commons; ‘you will do good service at London persuading the House to come nearer the King’, he declared on 6 November 1648 (CSP dom., 1648–9, 319). To no avail, for one month later the army violently excluded all those MPs in favour of the Newport propositions, Swynfen among them.

Following Pride's Purge, in which he suffered arrest and imprisonment, Swynfen found himself in the political wilderness; and his sense of bitterness was compounded still further by the regicide, for ‘he was always against the King's death’ (Lacey, 446). Such was Swynfen's disaffection that on 27 March 1651 the Rump council of state ordered his confinement in Denbigh Castle; but this was rescinded a few days later after he had agreed ‘to be of good behaviour’ and provide a £1000 surety (CSP dom., 1651, 114, 132).

Swynfen then held aloof from national politics; and not even a personal invitation in June 1654 from one of the lord protector's leading counsellors, Sir Charles Wolseley, who had a high opinion of his ‘abilityes for the management of publique affayres’, to serve as an ambassador in the Netherlands to promote the ‘Protestant interest’, would win him back (William Salt Library, Salt MS 608).

Swynfen busied himself in rebuilding his family's finances after the devastation of the civil wars when he reputedly ‘lost his whole estate’ (Parl. Arch., House of Lords MSS, special depositions, 2 May 1645). He also secured employment as the steward to Lord Paget, for which he received a yearly allowance of £100. By the late 1650s Swynfen had overcome his scruples over holding office: he was nominated a Staffordshire assessment commissioner in June 1657; and returned to the national stage with his election as MP for Tamworth in January 1659. His resentment against ‘swordsmen’ had still not abated, as was evident by the part he played in drawing up articles of impeachment against Major-General Boteler and in drafting proposals in April 1659 to secure the protector and parliament from any further military coups.

With the fall of the protectorate and the restoration of the Rump Parliament, Swynfen, along with other MPs secluded in 1648, was first excluded then, on 1 February 1660, readmitted to Westminster. Swynfen sat on the council of state from 25 February to 31 May 1660, was returned for Stafford in the Convention Parliament, and enjoyed a reputation for being one of ‘the old Parliament men’, though Sir John Bramston thought he was a ‘crafty’ politician when he and others ‘of that gang’ outmanoeuvred the younger, inexperienced MPs in the choice of speaker (The Autobiography of Sir John Bramston, ed. [Lord Braybrooke], CS, 32, 1845, 116). While he clearly welcomed the Restoration, playing a pivotal role in the parliamentary arrangements for Charles II's reception in London on his return from exile, Swynfen fought a rearguard action to protect presbyterian ministers like his brother Richard from ejection from the newly restored Anglican church, arguing for a modified episcopacy and religious comprehension in accordance with the Worcester House declaration of

25 October 1660. He also pleaded for mercy for those regicides who had voluntarily surrendered themselves despite his abhorrence at their crime, showing a ‘great moderation’ (Lacey, 446) which was evident in all the subsequent parliaments in which he served after the Restoration.

Swynfen survived the royalist landslide in the elections to the Cavalier Parliament early in 1661, this time sitting for Tamworth.

Though a somewhat isolated figure he continued to be an active member of the House of Commons ‘with 200 committee appointments, seven tellerships and over a hundred recorded speeches’ (Mimardière and

Henning) to his credit. Samuel Pepys described him in November 1662 as the ‘great Mr Swinfen, the parliament man’ (Pepys, 3.254). As a leading light in the small party of ‘old Presbyterians’ in the house (J. R. Jones, The First Whigs, 1961, 10–11) Swynfen still espoused the cause of godly reform and sponsored bills for stricter sabbath day observance. Protestant unity was another issue championed by Swynfen, who vigorously opposed the penal legislation against protestant dissenters on the grounds that they were ‘a people in communion with us in doctrine, though different in ceremonies’

(Lacey, 444). Swynfen grew ever more critical of the court, and by the mid-1670s was becoming increasingly concerned with the pro-Catholic direction of Charles II's policies.

Having retained his seat in the new parliament of March 1679 Swynfen was determined to apportion blame for the current political crisis over the Popish Plot, an alleged Catholic plot to kill the king, and the possible exclusion of the Catholic James, duke of York, from the succession. In a debate on 27 April he accused the entire episcopal bench of negligence ‘in the discovery of this horrible plot’ (Grey, 8.156). ‘Geneva, Geneva itself’, expostulated the outraged MP Sir Thomas Clarges, ‘could not more reflect upon the Holy Hierarchy than this gentleman’ (DWL, R. Morrice, Ent'ring book, 1.164). Not content with this Swynfen also singled out the duke of York as the man who had given most ‘encouragement to the whole Popish party’ through his open conversion to Catholicism (Grey, 8.156); and he fully backed the campaign to debar him from the throne. He helped to draft the Exclusion Bill and when it was debated in the Commons on 11 May roundly declared: ‘I take this case we are upon to be either the preservation or the ruin of the kingdom’ (ibid., 248). Swynfen was now clearly identified with the whig interest, but despite his party's triumph in the elections to the second Exclusion Parliament in August 1679 he was defeated in his Tamworth constituency by a single vote. He secured re-election to the third Exclusion Parliament in March 1681 and once more made his position absolutely clear on the question of exclusion, saying ‘I am for the Bill’ (ibid., 313).

The subsequent tory reaction prevented Swynfen from standing for election to James II's parliament in 1685, though he was one of the royal nominees for Tamworth three years later. But parliamentary service under James was anathema to Swynfen, who ‘absolutely declined to stand’ and in any case his candidature was rejected by the king's electoral agents on the grounds that he was ‘superannuated’

(Mimardière and Henning). Swynfen's steadfast opposition to James won him the belated approval of the Anglican establishment, the dean and chapter of Lichfield Cathedral declaring in 1687 that they had been ‘mistaken in him’ and now considered him ‘the fittest man to serve them’ in a parliamentary capacity; but Swynfen himself remained deeply suspicious of ‘the Churchmen’, who, he was convinced, were ‘not to be trusted’ (Lacey, 466). After the revolution of 1688 Swynfen sat in one more parliament, that of 1690–95, representing Bere Alston as a court whig. He was now a sick man, having suffered a stroke in 1687, and he died on 12 April 1694 at Swynfen Hall, Weeford, Staffordshire. He was buried the following day at St Mary's Church, Weeford.

Swynfen died a rich man, with lands in Staffordshire and Warwickshire worth at least £2000 per annum. His deep religious faith is evident in the familial injunction in his will: ‘I pray God guide and bless all my children and grandchildren that they may live in the fear of God and die in his favour’ (will, TNA: PRO, PROB 11/89/109). Swynfen was highly regarded by friend and foe alike: the presbyterian minister Edmund Calamy thought him ‘pious and judicious’, while an anonymous cavalier described him as a ‘very prudent and able man’

(Lacey, 144). But the finest tribute to Swynfen occurs on his funerary monument in Weeford church which proclaims that the object of greatest pride in his life was his lengthy parliamentary service which ‘he performed with singular honour and satisfaction to his country’ (Shaw, 2.25).

Swynfen's fifth son, Francis (d. 1693), and his wife, Jane Doughty (d. 1716), were the parents of Samuel Swynfen (1679/80–1736), physician. Samuel matriculated at Pembroke College, Oxford, on 31 March 1696 aged sixteen, graduated BA in 1699, MA from New Inn Hall in 1703, MB in 1706, and MD in 1712. He was a lecturer in grammar at the university in 1705. At Weeford on 18 November 1710 he married Mabel (d. in or after 1736), daughter and coheir of Ralph Fretwell of Hellaby, Yorkshire. They had twelve children baptized at Lichfield, where Swynfen had established himself as a physician by 1715. While living in Lichfield he became godfather to Samuel Johnson, the lexicographer. He afterwards moved to Birmingham and died there on 10 May 1736.

John Sutton DNB

Kneller was born Gottfried Kniller in Lübeck, Germany. His father Zachary Kniller was a painter and the Chief Surveyor of the city of Lübeck. In about 1662 he read mathematics at Leyden University before turning to painting, studying under Ferdinand Bol and probably Rembrandt. He was in Rome and Venice from 1672 to 1675, probably painting portraits of the Venetian nobility, before settling in England in 1676. There he ran a successful studio producing replicas and copies. After being introduced to the Duke of Monmouth, he received sittings from the king and was launched as a court artist, establishing a reputation as a portrait painter in the grand manner.

In 1684-5 Kneller was in France, painting Louis XIV for Charles II. A court painter to James II and George I, he was appointed principal painter to William and Mary in 1688. He was knighted in 1692, and in 1695 received, in the presence of the king, an honorary Doctorate of Law from the University of Oxford. In 1700 he was created a Knight of the Holy Roman Empire by the Emperor Leopold I. He married Susanna Grave, a widow, in 1704; the couple were childless. In 1711 he became Governor of the first London Academy, and was re-elected annually until 1718. George I granted Kneller a baronetcy in 1715. At the time of his death in London, about five hundred works remained unfinished in his studio.