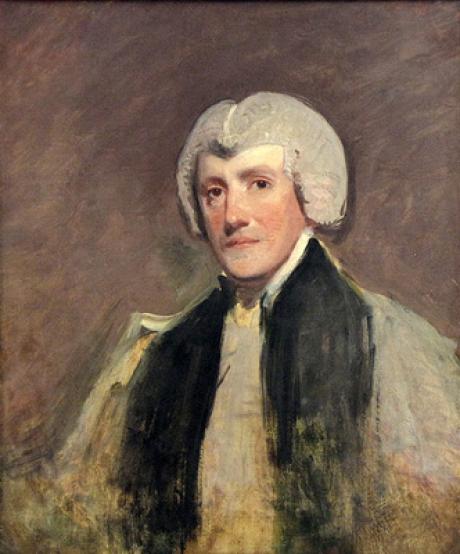

Portrait sketch for the full length portrait of manners-Sutton at Windsor Castle, circa 1795. (J Ingamells, English Episcopal Portraits p 372 type A1).

John Hoppner Studio Sale, Chritie's May 31st 1823

Viscount Canterbury, 1868

National Portrait Exhibition, 1868, No11 (incorrectly catalogud as by Sir Thomas Lawrence).

Charles Manners Sutton, - (1755–1828), archbishop of Canterbury, was born Charles Manners on 14 February 1755, the fourth son of Lord George Manners (1723–1783) and his wife, Diana (d. 1767), daughter of Thomas Chaplin of Blankney, Lincolnshire; he was grandson of John, third duke of Rutland. In 1762 his father assumed the additional surname Sutton on inheriting the estates of his maternal grandfather, Robert Sutton, second Baron Lexington. Educated at Charterhouse School, he then matriculated as a pensioner at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, on 1 March 1773; he graduated BA as fifteenth wrangler in 1777, his younger brother, Thomas Manners-Sutton, being at the same time fifth wrangler. He proceeded MA in 1780 and DD in 1792. In 1785 he was presented to the rectory of Averham with Kelham, Nottinghamshire, and also to Whitwell, Derbyshire. Manners-Sutton married in 1778 Mary (d. 1832), daughter of Thomas Thoroton of Screveton, Nottinghamshire. They had two sons and ten daughters.

Preferment was rapid. Manners-Sutton became dean of Peterborough in 1791, in 1792 bishop of Norwich, and—because Norwich had a small income and was a large and expensive diocese—influence at court secured him the deaneries of Windsor and Wolverhampton in 1794, to be held in commendam. He and his wife became great favourites with George III and the royal family. In 1794 he was offered the archbishopric of Armagh, but he declined the appointment. At Norwich, Manners-Sutton was a conscientious and well-liked diocesan bishop. He was the first bishop of Norwich consistently to undertake all his ordinations in Norwich. He was hospitable and generous to charities. He dined with his clergy after his visitations and treated them with wine, ‘a bottle between two’ (Diary of a Country Parson, 3.367). He separated confirmations from visitations. After a confirmation James Woodforde, rector of Weston Longueville, noted that his niece, ‘Miss Woodforde [was] much pleased … with the Bishop's very agreeable and affable, as well as polite and sensible behaviour’ (ibid., 4.141). In his visitations he demonstrated a keen interest in matters of contemporary concern to the church—the employment of curates; the administration of baptism, schools, and almshouses; and disputes over tithe payments—and he asked for any other Matters relating to your Parish of which it may be proper to give me Information, Or any proposal to make whereby the Glory of God and the Good of his Church may be promoted, and this Diocese better ordered, and ourselves mutually aiding and assisting each other in the Discharge of our respective Duties. (Visitation inquiries, 1801, Norwich RO, NDR VIS 39/17)

During the threat of French invasion in 1803 Manners-Sutton urged the clergy to warn the poor of the risks a French occupation might have for them, but he advised the clergy against joining militias or defensive corps. At Norwich, Manners-Sutton seems to have got into financial difficulties, despite the additional revenues of the deanery of Windsor, and he was criticized for extravagance.

On the death of Archbishop Moore in 1805 George III intervened personally with William Pitt to secure Manners-Sutton's translation to Canterbury, although Pitt wished to appoint his former tutor, Bishop Pretyman-Tomline of Lincoln. As archbishop Manners-Sutton played an active part in the policies of the traditional high-church party then ascendant in the church. He was himself a high-churchman: it was noted that at his primary visitation in Canterbury Cathedral in 1806 that he preached on the significance of confession and its history. Manners-Sutton played a central role in the series of initiatives and reforms to promote the church's mission in the period of dramatic social change brought about by population growth, urbanization, and industrialization. From at least 1809 he worked to secure government funds to build new churches to meet the needs of the rapidly expanding population. In the House of Lords he took an active part in the attempt to secure satisfactory legislation to provide adequate stipends for curates. With lay members of the Hackney Phalanx, notably Joshua Watson, and with the co-operation of the prime minister, the earl of Liverpool, he worked to secure the Additional Churches Act of 1818, which gave the Church of England £1 million to build new churches, although he was defeated by ministers in his wish that clergy should be in the majority on the subsequent commission for building new churches. He was one of the most regular attenders at the commission's committee meetings.

Manners-Sutton was also active with the Hackney Phalanx in reinvigorating existing voluntary bodies to promote the church's mission and in creating new bodies. The Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge was overhauled and Manners-Sutton played a significant part in the foundation of the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in 1811; he nearly always chaired the fortnightly meetings of the society's committee and he persuaded the prince regent to become patron of the society. The society provided a model for the church to act in a corporate capacity in the absence of the convocations, including all of the bishops as its vice-presidents, along with leading laymen. He was closely involved in the foundation of the Incorporated Church Building Society, of which he chaired the majority of meetings, to raise funds to provide grants for building and repairing churches to provide more seats in churches for the increasing population.

Manners-Sutton worked closely with the Hackney Phalanx to revive the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel and he was active in the campaign that secured the establishment of a bishop for India, being closely involved in recruiting Thomas Middleton, archdeacon of Huntingdon, and an associate of the phalanx, as first bishop of Calcutta. Manners-Sutton was also concerned with the extension of higher education. He contributed £1000 towards the endowment of King's College, London, and was instrumental in persuading George IV to give his name to the college; he also contributed towards the establishment of both St David's College, Lampeter, by Bishop Burgess of St David's and of King's College in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In 1814 he was appointed to preside over the German Relief Fund to administer a parliamentary grant of £100,000 for the relief of Germany during the winter of the final Napoleonic campaign, which—because of opposition to the grant in the light of needs for charity relief at home—needed to be a model of accurate accounting. Joshua Watson acted as administrator of the funds. In 1816 Manners-Sutton and Bishop Howley of London unsuccessfully attempted to revive the Association for the Relief of the Manufacturing and Labouring Poor, established in 1812, and in 1817 he briefly flirted with Robert Owen's plan to put the poor into ‘Villages of Co-operation’ where, after an initial capital grant from taxes, they would pay their own way while becoming useful, industrious, self-disciplined, and temperate.

Manners-Sutton may have been the initiator of a meritocratic revolution that reinvigorated the Church of England in the early nineteenth century. Although his own preferment was due to aristocratic patronage and royal favour, he, along with Bishop Howley of London, worked with Joshua Watson and his associates in the Hackney Phalanx to test the potential of able young graduates from middle-class backgrounds, making discriminate use of the extensive patronage available to archbishops of Canterbury and promoting the most promising candidates. His own chaplains provided able leaders for the next generation of high-churchmen: Christopher Wordsworth, subsequently master of Trinity College, Cambridge; George Cambridge, subsequently archdeacon of Middlesex; John Lonsdale, subsequently bishop of Lichfield; Charles Lloyd subsequently bishop of Oxford; Richard Mant, subsequently bishop of Down and Connor, and Hugh James Rose, subsequently principal of King's College, London. Manners-Sutton was however, bitterly attacked by radical pamphleteers for alleged nepotism in his use of patronage. Manners-Sutton was regularly consulted by Lord Liverpool about the appointment of bishops. He was a key figure in the queen's council appointed to review George III's health and in the complex relations between the queen and the doctors caring for the king, whom the queen distrusted. He attracted public hostility for supporting the bill for George IV's divorce on the grounds that divorces ‘were expressly declared by our Saviour himself’ (Varley, 97). He was also involved in the negotiations over the modifications to the liturgy for George IV's coronation. At the end of his life Manners-Sutton opposed Roman Catholic emancipation, but favoured the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts. At Canterbury he was reckoned to be generous in his charity and his hospitality, but he paid meticulous attention to the administration of the archiepiscopal estates, which included major developments at Dover and Deal. In 1808 he purchased Addington Place as a country seat for archbishops in succession to the palace at Croydon, which had been sold in 1780. He published two sermons in 1794 and 1797; An Address to the Clergy of the Diocese of Norwich, in 1803; and he contributed ‘A description of five British species of orabanch’ to the Transactions of the Linnean Society (vol. 4, 1797, 173). Archbishop Manners-Sutton died on 21 July 1828 at Lambeth Palace and was buried on 29 July at Addington parish church. His eldest son, Charles Manners-Sutton, became speaker of the House of Commons and subsequently first Viscount Canterbury, and his second son was a colonel in the army.

W. M. Jacob DNB

It is hard to imagine anyone more comprehensively a part of the aristocracy than the Right Reverend Charles Manners-Sutton, D.D., who was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1805 - 1828. His pedigree contains numerous Dukes, Earls, Knights of the Garter, and other lords and ladies.The grandson of a Duke, and a nephew of the famous Marquis of Granby, he was himself a member of the House of Lords from 1792. His younger brother, a former Solicitor General, was created Baron Manners in 1807. Subsequently, the Archbishop's elder son, having served as Speaker of the Commons for 17 consecutive years, was also ennobled with the title of Viscount Canterbury.Charles Manners-Sutton was also, via Lionel - a brother of the Black Prince - directly descended from Edward III, and therefore from William the Conqueror. Other ancestors include Ethelred the Unready and Saint Margaret of Scotland. A Dean at the age of 36 and a Bishop at 37, he was nominated as Archbishop of Canterbury when still only 49. In view of his importance and his many other commitments, it seems surprising that he agreed to come to Bognor - at that time only a hamlet and a tithing of Bersted - to consecrate not a church, but merely a chapel of ease to the parish church. However, come he did.

Hoppner, John (1758–1810), portrait painter, was born on 25 April 1758 in London, perhaps at St James's Palace, the first of the two children of John Hoppner, a surgeon, and Mary Anne (1728/9–1812). Hoppner's parents were both Germans—Bavarians according to the artist's son Belgrave—who came to England to serve in the court of George II. While Hoppner's place of birth is uncertain, he was baptized at Whitechapel, at that time a German Catholic ghetto in London, suggesting he may have been Roman Catholic.

Early years and education

Having spent his childhood at court, Hoppner associated easily with royalty throughout his career. Indeed rumours began during his own life that he was an illegitimate child of George III. While Hoppner never denied them (according to some he encouraged them, certainly for reasons of publicity), there is no credible evidence for a liaison between the twenty-year-old prince of Wales and Hoppner's thirty-year-old mother. Hoppner apparently had only one sibling, Elizabeth, who married the engraver J. H. Meyer; they were the parents of the engraver Henry Meyer.

Hoppner was a member of the Chapel Royal choir and was recommended as a ‘Lad of Genius’ (Farington, Diary, 2.286) to George III who provided him with an allowance. In 1775 he entered the Royal Academy Schools, winning a silver medal for drawing from life in 1778 and the gold medal for historical painting in 1781, when he completed his studies. He married Phoebe Wright (1761–1827), daughter of the wax sculptor Patience Wright (1725–1786), on 8 July 1781 and moved into Mrs Wright's waxworks in Cockspur Street, Westminster. Upon his marriage his royal allowance ended and by all accounts he struggled for some years. By Christmas 1783 Hoppner and his wife had moved into 18–20 Charles Street, between St James's Square and the Haymarket (now demolished), a fashionable address, which added to Hoppner's financial concerns.

1780–1790

At the Royal Academy Schools Hoppner was a contemporary of Patience Wright's son Joseph; Mrs Wright's studio functioned in many ways as a salon, in particular for artistic and whig personalities. While there is no account of Hoppner at the waxworks, it was clearly through his wife's family that he acquired a number of connections, both artistic and social. Hoppner began exhibiting at the Royal Academy in 1780, and continued annually (except in 1801 and 1808 for reasons of health) until 1809. While most of his early portraits depict gentry, by 1783 he was exhibiting portraits of nobility and in 1785 exhibited three portraits of the youngest daughters of George III, perhaps using his court connections to advantage. In 1786 he exhibited a full-length portrait of the duke of Clarence's actress mistress, Mrs Jordan as the Comic Muse (Royal Collection), in emulation of, or perhaps in competition with, Reynolds's celebrated portrait exhibited two years earlier, Mrs Siddons as the Tragic Muse.

In 1785 Hoppner published his first art criticism: unsigned reviews of works by Maria Cosway, Richard Cosway, and Benjamin West in the Morning Post. These were critical and condescending, though not contrary to prevailing opinion. Later revealed as the author, Hoppner was led to write his ‘Address to the public’ (Morning Post, 2 July 1785); there he described the difficulties under which he laboured when his royal allowance was withdrawn after his marriage, blaming West, who he thought was trying to rid himself of a rival.

In reality Hoppner was no one's rival in 1781, but his reputation steadily advanced throughout the 1780s. In 1787, when Gilbert Stuart abandoned London for Ireland to escape creditors, Hoppner was the artist widely considered the successor to Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough as the country's most respected portraitist. He was well connected socially; the duke of Clarence, Henry Lascelles, second earl of Harewood, Earl Grosvenor, and Viscountess Hampden all served as godparents for his children. During the late 1780s he crafted likenesses, primarily head-and-shoulders images, which were finely coloured and often noted for their dependence on Reynolds (although perhaps he owed more to George Romney earlier in the decade). In 1790 Hoppner had been recommended to Catherine the Great as the young British artist with the most talent: ‘Hoppner est celui parmi les jeunes Peintres qui parait avoir le plus de Talens’ (Soobshsheniya Gos. Ermitazha, 44). In the Royal Academy exhibition of 1790, however, Hoppner's two subtle heads of the Horneck sisters (Taft Museum, Cincinnati, and ex Sothebys, New York, 25 April 1985) were overshadowed by the two bold full-length portraits exhibited by the 21-year-old Thomas Lawrence of Queen Charlotte (National Gallery, London) and of the actress Elizabeth Farren (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Hoppner, caught unaware—as were his contemporaries—by the quality of Lawrence's work, spent the 1790s demonstrating his own powers both of painting and of attracting sitters.

1791–1800

With the fourteen paintings entered in the exhibitions of 1791 and 1792, Hoppner did indeed demonstrate the full range of his work, with ten of the sitters being royal, a royal mistress, or noble (two others were subject pictures). By 1793 he had succeeded Reynolds as portrait painter to the prince of Wales, a more popularly prestigious appointment than portraitist to the king (which went to Lawrence), and was elected an associate of the Royal Academy. In 1795 he was elected an academician and his prestige was such that the king commissioned him, rather than Lawrence, to paint a portrait of the new princess of Wales, an opportunity Hoppner lost by responding aggressively to some of the king's art criticism.

Even without the patronage of the king, Hoppner was extremely successful in the 1790s, making over £2000 a year in 1798 and £3000 in 1801. He was patronized by all sectors of society: tories and whigs, politicians, the military and clergy, the elderly, and the parents of children and young beauties. By all accounts he was handsome and a brilliant conversationalist, not only amusing and animating his sitters but active in several clubs and in the political and social life of the Royal Academy. Hoppner took an active role in running the academy, taking his turn at serving on the council and as a visitor to the schools, and with other ad hoc groups such as that which investigated the validity of the notorious ‘Provis's process’ or the ‘Venetian secret’, a recipe for mixing paints in the manner of Titian.

Hoppner's technique and style derived from the teachings of Reynolds, but neither in technique nor in style did he follow the elder painter slavishly. As a student and in his early maturity (when his style owed more to Romney and Johan Zoffany) Hoppner would have heard Reynolds deliver his Discourses; but while Reynolds held up the work of Michelangelo and the Florentine Renaissance as a model for artists, Hoppner preferred the Venetian and Flemish painters, such as Titian and Van Dyck, or the more painterly aspects of Rembrandt, all of whose works Hoppner knew at first hand from the Royal Collection; these Reynolds advocated only with caution for their ‘seductive’ qualities. While Reynolds taught that artists should work in an academic method of preparation with drawings and sketches, Hoppner (as did Reynolds himself) began his portraits directly from life onto the final canvas and worked them up to completion, only occasionally making a study of the sitter first. Hoppner's studio was described by the French artist Henri-Pierre Danloux in 1792:

his gallery is small and sombre, as are all those of the English … The light came in from above and one could hardly distinguish a thing. I was surprised at this lack of light; he said to me that he could see perfectly and it was the true way of getting the effect. (Portalis, 94)

Hoppner took an interest in younger artists, freely offering advice as he did to Turner (who gave him a watercolour in thanks for his help), or taking them into his studio, as he did with Henry Salt. Constable recorded Hoppner's help on the verso of a portrait of Richard Ramsay Reinagle (ex Sothebys, London, 10 November 1993); J. J. Halls recorded that he had an open invitation to Hoppner's studio; and David Wilkie's journals imply that he, Constable, and Benjamin Robert Haydon were all welcomed by Hoppner. Two of Hoppner's children exhibited as artists: Lascelles Hoppner (who likewise won the Royal Academy's gold medal and later took over his father's studio), and Richard Belgrave Hoppner [see below].

1801–1810

Hoppner fell from his coach and broke his arm in 1801, causing him to exhibit nothing that year, and the first decade of the nineteenth century was a period of considerable success but also of declining health. Hoppner's health had caused concern from an early age; a contemporary wrote that he became an artist because he did not have ‘sufficiently good health to follow the profession of music’ (Papendiek, 1.232). The diarist Joseph Farington first noted Hoppner's tenuous health in 1795, and throughout the first decade of the 1800s he records a variety of ailments, most notably with Hoppner's liver, but also including ‘Hectic Fever’, ‘debility and want of Appetite’, and ‘dropsy’, for which Hoppner consulted several eminent physicians, among others Matthew Baillie, Sir Everard Home, Erasmus Darwin, and William Jenner. In 1807 he complained that his health was preventing him from finishing a portrait of the prince of Wales, and he did not exhibit at the Royal Academy in 1808. In 1809 he exhibited portraits executed earlier.

Hoppner painted some of his most celebrated works between 1802 and 1807 after his only trip abroad: to Paris during the peace of Amiens. In Paris he visited the Louvre, and despite his knowledge of the old masters in the British Royal Collection he was unprepared for the quality of the works of art assembled by Napoleon. On his return Hoppner worked with new attention to primary colours and simple compositions, in particular in life-scale, head-and-shoulders portraits of men. His portraits were frequently remarked upon for their likeness, even when the composition as a whole was unsatisfactory. Referring specifically to Hoppner's portrait of William Pitt, the portraitist William Owen described Hoppner's qualities of likeness in relation to those of other artists. Owen

wondered Hoppner had dared so strongly to express a character in Mr. Pitt's countenance in which Hauteur and something of disdainful severity were so predominant.—It was the truth but others had as usual, when any disagreeable tendency was manifested in the countenance, endeavoured to soften it. (Farington, Diary, 7.2693)

Hoppner's portrait of Nelson (1800–01; Royal Collection) was not only considered a good likeness, but took on an enhanced popularity when it was engraved by Charles Turner after Nelson's death and published in 1806.

Hoppner's last years were occupied by the political turmoil at the Royal Academy surrounding Benjamin West's presidency in 1805; Hoppner voted inconsistently during this period. This, combined with his increased irritability caused by health problems, caused him to paint less and write more, spending less time with his established circle of academician friends. His intellectual social life centred on younger artists, literary friends, and clubs; he was a member of the Athenian Club, the Council of Trent (limited to thirty members), and the King of Clubs. Moreover, he was proposed for the Royal Society in 1797 and the Literary Club in 1799, but was not elected to either, according to Farington, because he was an artist. He counted among his friends several eminent poets and literary critics. Hoppner painted a handful of exceptional full-length portraits, most notably of admirals Sir Samuel Hood (1807; NMM) and John Jervis, earl of St Vincent (Royal Collection), both of whom were portrayed in a sympathetic and thoughtful manner. His smaller works, particularly those portraying acquaintances, were frequently rendered in a penetrating style with clear colours—as in portraits of Sir George Beaumont (1803; National Gallery, London) or his friends from the King of Clubs such as Samuel Rogers (1809; priv. coll.). Occasionally, however, they displayed a remarkable energy of brushwork, as in portraits of the third duke of Grafton (1805) or Lady Caroline Lamb (c.1806; both priv. coll.).

Hoppner had resumed his writing career by the late 1790s, when Farington recorded his work in the British Critic. By that time he had also begun writing Arabic-themed poetry; at least one of these poems was published in The Pic-Nic. He published these verses as a group in 1805 as Oriental Tales, but they are better known for the notorious preface to the first edition. In the preface Hoppner justified his own style and method of painting—which had often been criticized as unfinished—in contrast to the contemporary French school, in particular the work of J. L. David and Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (the latter then working in England), and which he savaged. In 1807 Hoppner wrote for Prince Hoare's The Artist, and late in his life reviewed books on art for the Quarterly Review.

Hoppner's art collection included a few distinguished works, among them Gainsborough's portrait of Jonathan Buttall (‘The Blue Boy’; Huntington Library, San Marino, California), Van Dyck's portrait of François Langlois playing bagpipes (National Gallery, London), and a portrait of Sir Theodore Mayerne, then thought to be Rubens's original (North Carolina Museum of Art).

Hoppner's health declined substantially in the summer of 1809 on a holiday to the Isle of Wight; in June he suffered what William Gifford described as an apoplectic fit. In mid-January 1810 he was extremely lethargic and tried to work so as to keep from sleeping constantly (Farington, Diary, 10.3594). He fell into a coma about three days before his death at his home, 18–20 Charles Street, London, on 23 January 1810. He was buried at St James's churchyard, Hampstead Road, London, on 29 January after a private funeral. Little public notice was taken of his death.

Reputation

Owing in part to Sir Thomas Lawrence's spectacular portraits of the 1810s and 1820s, and Hoppner's own less flamboyant style, Hoppner's reputation flagged throughout most of the nineteenth century. It was revived somewhat at the turn of the twentieth century with interest in grand-manner British portraiture collected by the Rothschilds, the Huntingtons, the Mellons, and the Fricks, among others. Portraits by Hoppner that most resembled those by Reynolds were the most sought after. His full-length portrait of Lady Louisa Manners (Musée de l'Art et d'Histoire, Geneva) was sold in 1901 for 14,050 guineas, at that time the record price for a picture sold at auction. With the decline of interest in society portraiture after the First World War Hoppner's reputation all but disappeared. His one appearance in late twentieth-century popular culture was his inclusion in Alan Bennett's play The Madness of George III (1991); the character was written out of the subsequent film.

(Richard) Belgrave Hoppner (1786–1872), diplomatist, was born on 9 January 1786 in London, the second among the five children of John Hoppner and Phoebe Wright. Belgrave Hoppner, as he was known, was named after his godfather, Richard Grosvenor, first Earl Grosvenor, whose courtesy title was Viscount Belgrave. He was educated at Eton College and received some artistic training from his father, exhibiting marine paintings at the Royal Academy, as an honorary exhibitor, in 1807, 1810, and 1811. He also exhibited twenty-one paintings at the British Institution.

Belgrave Hoppner's diplomatic career began in 1801 when he received a clerkship in the Foreign Office. He served as secretary to a variety of foreign missions in Spain, the Netherlands, and at the Council of Vienna. On 3 September 1814 he married Marie Isabelle (d. 1869/70), fourth daughter of Beat Lois May, seigneur d'Oron et de Brandis, of the canton of Bern, Switzerland, at the residence of the British ambassador in Brussels. They had a daughter, Emily. That year he was appointed consul general at Venice where his friendship with Byron, for which he is now chiefly remembered, was formed. Hoppner was on familiar terms with the poet by September 1817 when Byron leased the Hoppner villa in the Euganean Hills near Este. Byron was godfather to Hoppner's son, prompting the lines ‘On the birth of John William Rizzo Hoppner’ in February 1818. For six weeks from mid-May 1818 the Hoppners took temporary care of Allegra, Byron's illegitimate infant daughter with Claire Clairmont, repeating this kindness occasionally until Byron placed her in a convent. Hoppner was one of Byron's confidants during the poet's years in Italy, expressing candid disapproval of his relationship with Teresa Guiccioli, riding and swimming with him (most notably in Venice during Byron's contest with Cavalier Angelo Mengaldo, a 4½-mile swim from the Lido to the end of the Grand Canal near Santa Chiara), administering Byron's financial affairs while the poet was living in Ravenna, and sharing Byron's then low opinion of Venice.

Belgrave Hoppner suffered from frail health (Byron noted how thin he was), a trait he shared with his father, and he blamed much of it on the Venetian climate. He frequently asked for other assignments, but retired to London in July 1825. He was appointed consul general in Lisbon in 1830 during the Portuguese civil war; at a time when there were no formal diplomatic relations with Portugal he functioned as an ambassador. He returned to London in 1833 and took on no further appointments. Hoppner's hundreds of dispatches from his appointments survive in the Public Record Office; Voyage around the World, his translation of Ivan Fedorovich Kruzenshtern's account, was published by John Murray in 1813 and an ‘Elegy’ was praised by Byron in 1817 as ‘remarkably good’. His recollections and letters were the basis for much of the early biographical material for his father; his descendants own several of his letters.

Upon his retirement Belgrave Hoppner lived for some years in Grenoble. By 1860 he was living in Versailles and in 1871, after his wife's death at some time between October 1869 and January 1870, he moved to Turin. He died there on 6 August 1872.

John Wilson DNB